The Struggle for Existence

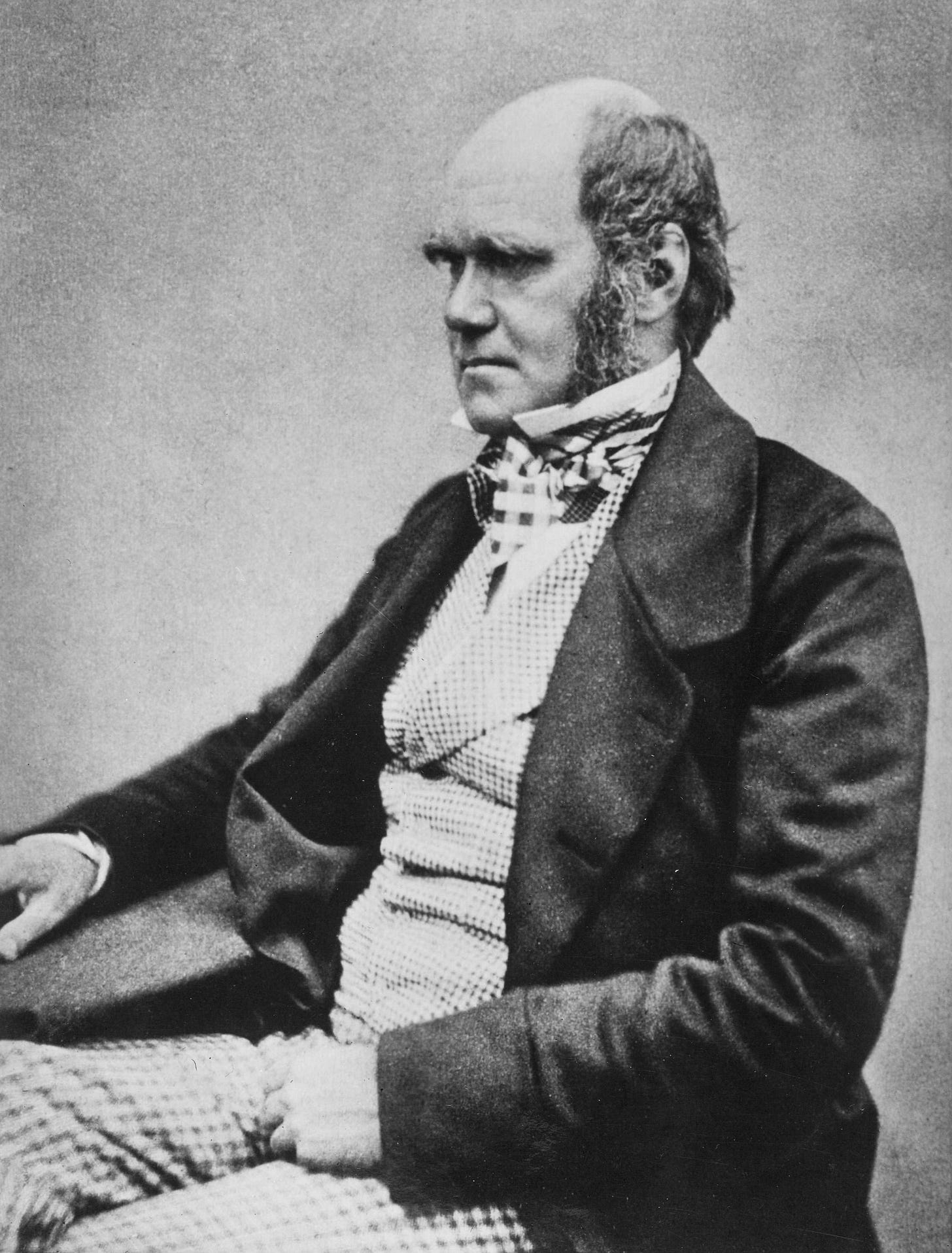

Ayn Rand and Charles Darwin

One of the upsides of having to move timely political commentary to my campaign site (expect a statement on the shooting in Minneapolis and several other things) is that it requires me to move forward on some intellectual projects that have been on the back burner for the past year.

I just posted the next chapter of my Prophet of Causation book in progress, which has still been moving slowly, even while I was busy charting the collapse of the republic, but which I’m now starting to bring over the finish line—at last as a polished draft. I am sure there will be some more tweaking before final publication.

This chapter returns to where I started, discussing the foundation of Ayn Rand’s ethics.

For this newsletter, I’ll share one part: my discussion of why I think Ayn Rand’s ethics is dependent on the discoveries of Charles Darwin, and it’s way more subtle than you might think. It’s not some kind of “Social Darwinism” or a crude application of the “survival of the fittest” (both of which, despite some popular caricatures, she fundamentally rejected in her ethics—but that’s for another chapter).

It’s about a certain way of looking at life and at what it means to be a living being. Here’s an excerpt.

Ayn Rand herself was curiously aloof about Darwin, disavowing any opinion about the theory of evolution. I suspect this is because in her day, Darwin was strongly associated with the kind of “evolutionary psychology” of the kind we discussed in the last chapter, but even more blatantly and rigidly determinist, which made her leery of any association with it. Yet the element of Ayn Rand’s morality that is historically most striking and unique is its use of a fundamentally biological perspective of human nature that was prevalent only after Darwin. He established the conceptual framework for Ayn Rand’s approach to morality by defining human life in terms of the needs and requirements of biological survival.…

What Darwin’s theory captures is that the main issue facing every kind of living being is survival. More important, the identity of that species, its very nature, was formed in the first place by the requirements of its survival. If an animal has a long beak or a short one, two legs or four legs, hair or feathers—each of these characteristics develops because it serves the requirement of survival.

It is hard to grasp today how radical and new this was, because we don’t really remember the previous way of thinking about nature. The Wikipedia entry for On the Origin of Species puts it rather well.

Historians have noted that naturalists had long been aware that the individuals of a species differed from one another, but had generally considered such variations to be limited and unimportant deviations from the archetype of each species, that archetype being a fixed ideal in the mind of God. Darwin and Wallace made variation among individuals of the same species central to understanding the natural world.

This also has some interesting implication for epistemology and the final defeat of the Platonist idea of abstractions as metaphysical archetypes. I’ll have to follow that up some other time. But back to ethics.

In this Darwinian outlook, the nature of man is not determined by some abstract archetype handed down by a higher power, a leftover element of Platonism. Instead, we are thoroughly shaped in our nature, down to the smallest detail, by the requirements of survival.

This gives specific and literal substance to the idea that every animal has a “natural function.” The concept of natural function is replaced by that of a means of survival, the characteristic actions by which a living being uses the natural traits that were propagated because they improved its ability to survive.

Ayn Rand was influenced, implicitly and indirectly, by this shift in thinking. She once said that she could not have come up with her philosophy before the Industrial Revolution, because it gave her the evidence she needed about the role of the mind in production. I would suggest that she could not have come up with her philosophy before Darwin, because he swept away the old archetypal thinking about human nature and replaced it with a theory in which the requirements of survival is the central concept of biology—and of human life.

If you’ve subscribed, you can read the whole article to see how this allowed Ayn Rand to go beyond the ethics of Aristotle and John Locke, as well as what I think is the clearest, most thorough answer to David Hume’s old dilemma about the “Is-Ought Gap.” Some of you might also appreciate the Douglas Adams reference at the beginning.

Next up in this project will be my chapter on Ayn Rand’s unique view of the nature of virtue.

I read a biography of Rand written by, what I took to be, a fair but skeptical political liberal, as I am generally. I liked the book but am interested in what a more supportive person say.

Looking forward to the book!