The True Party of the “Working Class”

Notes on “Main Currents of Marxism,” Part 1

When I announced my campaign for Congress recently, I said I would still be posting here at this newsletter, but on issues that were less tied in to the politics of the day. If you want that, go sign up on the campaign site.

Oh, and while I’m campaigning, The UnPopulist will continue the Executive Watch as an unsigned group blog. See the latest roundup here, and make sure you’re following them.

Today, I’m beginning the first of a couple of series where I’ll be drawing lessons from books I’ve read in the past few years. The first series will be on Main Currents of Marxism, by Leszek Kołakowski. This work not only presents Marx’s ideas but puts them into a wider context in the history of philosophy—starting all the way back with the Ancient Greeks—and puts them in the context of the debates of Marx’s time, including competing socialist theories and the different strains of Marxism that broke off from his original theory.

I wish I could say this is a light and breezy read, but it’s not. It was originally published in three volumes, and this version combines them into a vast 1200-page brick of a book. And it’s not just long, it’s dense. Let’s put it this way. I took up this book a few years ago because I realized that after years of staying up writing far into the night to meet deadlines, it would probably be good if I made a habit of getting more regular sleep. But I’ve always got so many projects going on that I find it difficult to get that all out of my head and calm myself down at the end of the night. I needed something to read that would be dense and absorbing enough to drown out everything else—but not so engaging that it gets me spun up about interesting new ideas.

Boy, did this book do the trick. It took almost a year to read, because I could only do it four to six pages at a stretch. That’s as much as I could handle before lapsing into a coma. It’s not Kołakowski’s fault, really, it’s the subject matter. Marxist philosophy is abstruse and pretty disconnected from anything in the real world. So there’s no way to make this a page-turner.

Yet there are some very interesting observations that I pulled out of the book. Look at it this way: I happily sacrificed my wakefulness for the better part of a year in order to distill a few useful lessons from this book, while saving my readers the prospect of slogging through hundreds of pages of arcane philosophy. It’s a win-win.

I want to spend this first installment (of four) setting some of the context for the book.

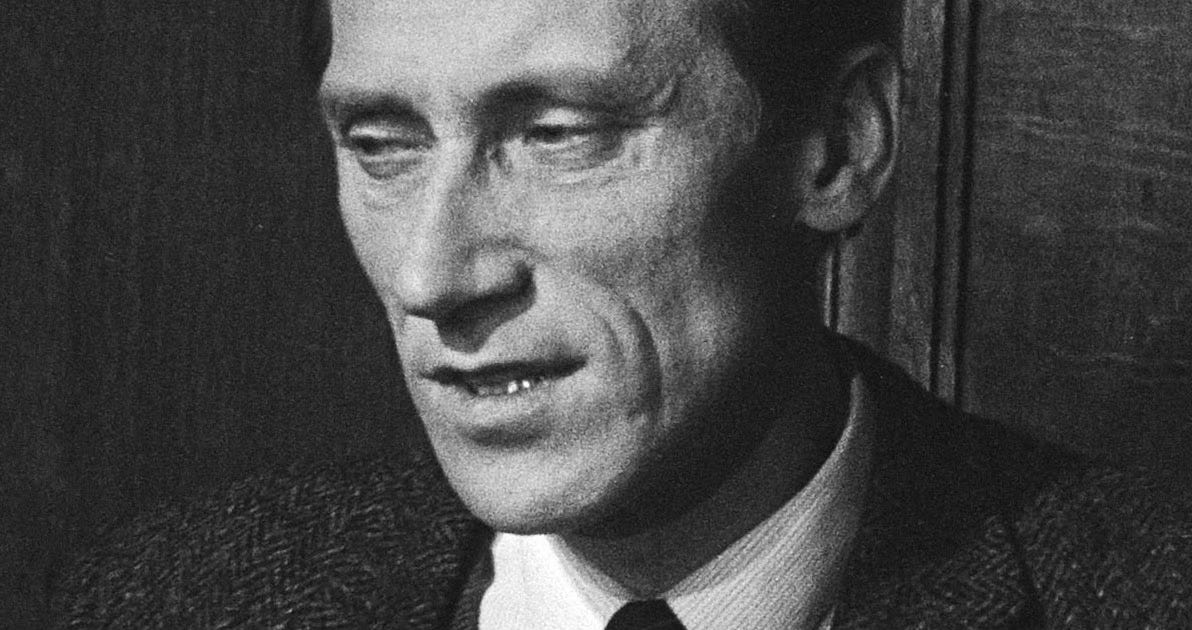

Leszek Kołakowski was a dissident East Bloc academic who wrote this book in the 1970s after being exiled from Poland and ending up at Oxford.

Strangely, writing a detailed book on the intellectual history of Marxism was itself a dissident act. Communist intellectuals in the Soviet Union and in Soviet-dominated countries like Poland were not encouraged to make a detailed and probing study of the history and development of Marxism, because doing so might encourage critical thinking about Marxism.

I have long held that the worst thing that can happen to any ideology is for it to win political power and become an official dogma imposed from above, because this is precisely what kills thinking about that ideology and reduces it from a living idea to a rote formula to be memorized. That is exactly the fate suffered by Marxism—East of the Iron Curtain, at least—when it became the official doctrine of the Soviet Union.

Kołakowski has some interesting things to say about this, which I will save for a future installment. What’s important for now is that looking firsthand at Marx’s original writings—including early writings, obscure publications, and lost manuscripts that were not widely available until the middle of the 20th Century—produced a different and more complex version of Marxism. It’s a version that did not cohere with the official doctrines, so studying the real Marx became a subversive act in a nominally Marxist dictatorship. Which is ironic, right?

One of the things that is most interesting is the way Kołakowski places Marx’s doctrines within the intellectual environment of the leftist movements of the 19th Century. Every movement always looks more monolithic to an outside observer than it really is, and people tend to talk about how “the left” thinks this or “the right” thinks that, without realizing the many internal schisms and debates within these movements. In reality, an ideology like Marxism is shaped to a significant degree in response to internal debates within the wider left-wing movement of its time.

In the historical context of Marx’s time, the key dividing line is between “socialism” and “social democracy.” That’s a history that was very important in Europe and shaped most contemporary European societies. But it is not all that well-known in America.

Karl Marx was the leading figure in the international socialist movement in the second half of the 19th Century. But he was the leader of the revolutionary socialists, who were breaking off from the “social democrats.” What is the difference?